You can embed photos, videos, and recordings of unusual or exciting birds to your checklists.

If you have a photo sharing website you can find the URL of your image and insert it directly as:

HTML code: <img src="http://your-photo-sharing-site/your-photo-name.jpg" />

If you use Flickr you can use the "share" function and copy the code.

Here are two things to remember:

1) Add the photo to the species comments section for each species (NOT checklist comments).

2) Use "medium" size (about 400x400 pixels).

3) Use no more than 2 photos per species.

Example eBird list with several photos embedded.

There are two pages on the eBird site that will provide more details.

http://ebird.org/content/ebird/news/embed-photos-in-your-checklists

http://help.ebird.org/customer/portal/articles/973966-adding-photos-videos-and-recordings-to-checklists

Enjoying and learning about birds in British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and northern California

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Beginning Bird Identification

Back in January 2012 I discussed how birds that look alike aren't always placed in field guides next to each other (Field-friendly bird sequence: Part one). Instead, they are arranged by presumed relationships (taxonomic order)--and these constantly changing.

Next I looked at some previous attempts to organize birds by general external physical characters. I proposed a sequence that placed all North American birds into 13 categories (Field-friendly bird sequence: Part two). Beginners should be able to quickly place a bird they see into one of these categories, then search for the exact species more accurately than in field guides ordered in taxonomic sequence.

Over the subsequent year I discussed one of the 13 categories each month. It is now completed. I've gone back and updated Part two with links to each discussion. I repeat it below for your convenience.

Swimming Waterbirds

Flying Waterbirds

Wading Waterbirds

Chicken-like Birds

Raptors

Miscellaneous Landbirds

Aerial Landbirds

Flycatcher-like Birds

Thrush-like Songbirds

Chickadee and Wren-like Songbirds

Warbler-like Songbirds

Sparrow and Finch-like Songbirds

Blackbird-like Songbirds

What do you think? Do you find these categories useful for beginning birders?

Next I looked at some previous attempts to organize birds by general external physical characters. I proposed a sequence that placed all North American birds into 13 categories (Field-friendly bird sequence: Part two). Beginners should be able to quickly place a bird they see into one of these categories, then search for the exact species more accurately than in field guides ordered in taxonomic sequence.

Over the subsequent year I discussed one of the 13 categories each month. It is now completed. I've gone back and updated Part two with links to each discussion. I repeat it below for your convenience.

Swimming Waterbirds

Flying Waterbirds

Wading Waterbirds

Chicken-like Birds

Raptors

Miscellaneous Landbirds

Aerial Landbirds

Flycatcher-like Birds

Thrush-like Songbirds

Chickadee and Wren-like Songbirds

Warbler-like Songbirds

Sparrow and Finch-like Songbirds

Blackbird-like Songbirds

What do you think? Do you find these categories useful for beginning birders?

Friday, April 19, 2013

How to identify hawks and other raptors

Review: The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors

|

| Photo from Princeton University Press. |

The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors (April 2013) is a 340 page book book covering the identification of 34 species of hawks, eagles, falcons, kites and other raptors found north of Mexico. As in the original Crossley guide, each page is like a museum panorama of dozens of bird photos backdropped by a photo of some well-known (often) North American scenic location. Most photo collages are 2-page spreads.

More than half the book is made of photo panoramic plates. The photos start with a couple of plates explaining the identification of each species and age. That is followed by a photo quiz plate! There are over 30 double-page plates of raptor quizzes, averaging more than 10 birds per quiz!

Whereas the original Crossley guide forsook text for photos, about a third of the book is textual species accounts written by raptor ID experts Jerry Ligouri and Brian Sullivan. Each species account begins with an interesting first-person introduction written from the perspective of the raptor itself--very unique! Subsequent sections in the species account include an overview, flight style, shape and size, plumage, geographic variation, molt, similar species, hybrids, status and distribution, migration, and vocalizations. Large 3-color maps show the breeding, resident, and winter ranges. The final 20 pages or so give the answers to the photo quizzes.

Three books in one!

- Annotated ID plates similar to the original Crossley ID Guide to birds.

- Expert in-depth species accounts covering status, distribution, and detailed plumage and flight style ID.

- Photo quizzes and answers.

For your convenience you can follow the link below to order this book from Amazon. And, yes, a very small percentage of the sale will go to me.

Labels:

bird books,

field guides,

reviews

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

No Swainson's Thrushes before May!

All Swainson's Thrushes reported before April 28 in the Pacific Northwest are probably misidentified.

There. I said it. It may not be absolutely true, but true enough that if you think you saw one before May you better make doubly sure. In fact, it is possible that many Swainson's Thrushes reported before May 8 are in error, too.

In February I wrote a blog post for Birding is Fun! titled: Ten most-misidentified birds in the Pacific Northwest. The number one identification problem mentioned by a group of knowledgeable birders was the misidentification of Hermit Thrushes as Swainson's Thrushes.

Swainson's Thrushes vacate North America in late fall and do not come back until late spring. Nevertheless, numerous beginning birders every year report Swainson's Thrushes in April and even March. Hermit Thrushes are abundant early spring migrants and winter in good numbers in wooded areas west of the Cascades. Swainson's Thrushes nest in lowlands, Coast Range, and lower mountain slopes with deciduous or mixed woods. Hermit Thrushes in the Pacific NW nest in high elevation evergreen forests from the Cascade crest eastward (also in higher Olympic Mountains of Washington).

Take a look at the photos below. Do you see why many people have trouble telling these apart?

If you happen to have the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 6th Edition (2011), the Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America (2010), or the New Stokes Guide: Western region (2013) compare the Pacific coast (ustulatus) form of Swainson's Thrush and the western lowland (guttatus) form of Hermit Thrush. These are the two forms found most commonly west of the Cascades and look most alike.

Hermit Thrushes have slightly darker, rounder breast spots, and a reddish rump. Swainson's Thrushes have a pale supraloral area (the lores is the area between eye and bill, supraloral is above that). It makes the Swainson's Thrush look like it is wearing spectacles. Trouble is, this isn't that distinctive (see above photos). It doesn't help that these birds are shy and hide in the thick, shaded, understory shrubs.

East of the Cascades the subspecies look slightly less similar, but the Swainson's Thrushes east of the Cascades migrate even later in spring than those west of the Cascades.

Calls and songs are different. But Starlings and other birds can imitate the Swainson's Thrush's mellow whistled "whit" call. Hermit Thrushes give a blackbird-like chuck call.

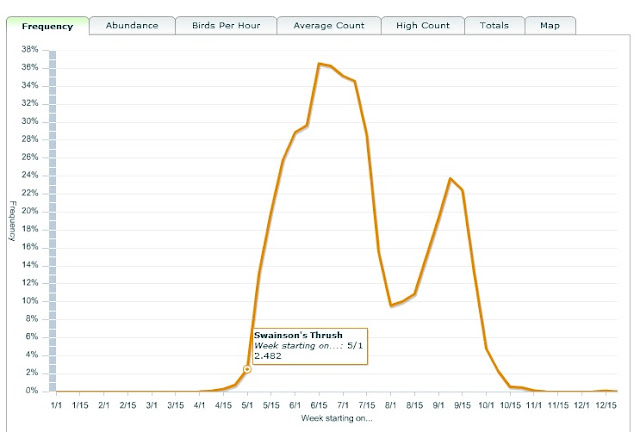

Notice the eBird history for Willamette Valley, 1900-2013 (above). Only a very few Swainson's Thrushes show up the first week of May; most arrive later in May. Earlier reports are either exceptionally early birds or (probably) misidentifications.

Let's look at just the last 5 years for all of Oregon.

There are a couple of things to note here.

1) The reports in March and early April are probably misidentified. Even if some are correct, they make up less than 1% of checklist frequency. Consider it data "noise."

2) Ignoring the early noise, the first birds for the year didn't arrive until the first week of May in 4 of 5 years. In 2008, perhaps due to weather conditions, Swainson's Thrushes arrived in western Oregon some time during the fourth week of April (April 22-30th; see the label on the above graph).

3) Notice the peak frequencies in the fourth week of May (migration) and the third week of June (territorial singing). Then notice more detections as they migrate south in September and are heard by birders at night as they fly over calling "weet."

4) A single bird with injured wing photographed in Portland in December 2008. Healthy birds are highly unlikely in winter anywhere in North America.

So that's it. Question the correctness of your identification of Swainson's Thrushes before mid-May. Try to really study both these rather common woodland and forest birds this summer and learn their calls, songs, behavior, and habitat. It's always fun to be the first one on your block (I mean, listserv) to report the arrival of a new spring migrant. It's better, though, to actually be correct.

There. I said it. It may not be absolutely true, but true enough that if you think you saw one before May you better make doubly sure. In fact, it is possible that many Swainson's Thrushes reported before May 8 are in error, too.

In February I wrote a blog post for Birding is Fun! titled: Ten most-misidentified birds in the Pacific Northwest. The number one identification problem mentioned by a group of knowledgeable birders was the misidentification of Hermit Thrushes as Swainson's Thrushes.

Swainson's Thrushes vacate North America in late fall and do not come back until late spring. Nevertheless, numerous beginning birders every year report Swainson's Thrushes in April and even March. Hermit Thrushes are abundant early spring migrants and winter in good numbers in wooded areas west of the Cascades. Swainson's Thrushes nest in lowlands, Coast Range, and lower mountain slopes with deciduous or mixed woods. Hermit Thrushes in the Pacific NW nest in high elevation evergreen forests from the Cascade crest eastward (also in higher Olympic Mountains of Washington).

Take a look at the photos below. Do you see why many people have trouble telling these apart?

|

| Swainson's Thrush. 28 June 2008. Timber, Oregon by Greg Gillson. |

|

| Hermit Thrush. 17 December 2010. Hagg Lake, Oregon by Greg Gillson. |

Hermit Thrushes have slightly darker, rounder breast spots, and a reddish rump. Swainson's Thrushes have a pale supraloral area (the lores is the area between eye and bill, supraloral is above that). It makes the Swainson's Thrush look like it is wearing spectacles. Trouble is, this isn't that distinctive (see above photos). It doesn't help that these birds are shy and hide in the thick, shaded, understory shrubs.

East of the Cascades the subspecies look slightly less similar, but the Swainson's Thrushes east of the Cascades migrate even later in spring than those west of the Cascades.

Calls and songs are different. But Starlings and other birds can imitate the Swainson's Thrush's mellow whistled "whit" call. Hermit Thrushes give a blackbird-like chuck call.

|

| Swainson's Thrushes reports in eBird for the Willamette Valley of western Oregon. |

Notice the eBird history for Willamette Valley, 1900-2013 (above). Only a very few Swainson's Thrushes show up the first week of May; most arrive later in May. Earlier reports are either exceptionally early birds or (probably) misidentifications.

Let's look at just the last 5 years for all of Oregon.

|

| eBird graph of Swainson's Thrushes in Oregon, 2008-2012. |

1) The reports in March and early April are probably misidentified. Even if some are correct, they make up less than 1% of checklist frequency. Consider it data "noise."

2) Ignoring the early noise, the first birds for the year didn't arrive until the first week of May in 4 of 5 years. In 2008, perhaps due to weather conditions, Swainson's Thrushes arrived in western Oregon some time during the fourth week of April (April 22-30th; see the label on the above graph).

3) Notice the peak frequencies in the fourth week of May (migration) and the third week of June (territorial singing). Then notice more detections as they migrate south in September and are heard by birders at night as they fly over calling "weet."

4) A single bird with injured wing photographed in Portland in December 2008. Healthy birds are highly unlikely in winter anywhere in North America.

So that's it. Question the correctness of your identification of Swainson's Thrushes before mid-May. Try to really study both these rather common woodland and forest birds this summer and learn their calls, songs, behavior, and habitat. It's always fun to be the first one on your block (I mean, listserv) to report the arrival of a new spring migrant. It's better, though, to actually be correct.

Labels:

identification,

Swainson's Thrush

Monday, April 15, 2013

Field-friendly bird sequence

Blackbird-like Songbirds

|

| Brown-headed Cowbird, Hines, Oregon, May 24, 2009 by Greg Gillson. |

Swimming Waterbirds

Flying Waterbirds

Wading Waterbirds

Chicken-like Birds

Raptors

Miscellaneous Landbirds

Aerial Landbirds

Flycatcher-like Birds

Thrush-like Songbirds

Chickadee and Wren-like Songbirds

Warbler-like Songbirds

Sparrow and Finch-like Songbirds

Blackbird-like Songbirds

A beginner should be able to quickly place a bird they see into one of these categories.

Smaller than crows, blackbirds, starlings, and cowbirds are primarily black in color.

Red-winged Blackbird, Sherwood, Oregon, May 9, 2009 by Greg Gillson.

Great-tailed Grackle, Hines, Oregon, May 23, 2009 by Greg Gillson.

European Starling, Forest Grove, Oregon, April 11, 2009 by Greg Gillson.

Labels:

field friendly sequence,

identification

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Review: "New" Stokes Field Guides -- East and West

I was quite impressed with the 2010 Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America. So when Lillian Stokes asked me to review their new (2013) Eastern and Western field guides I looked forward to it with great anticipation.

The reason the 2010 Stokes guide was so good was that it used numerous photos of different plumages. Additionally, it was the first field guide to really describe all the variations of subspecies--with photos of many different-looking forms. The book had ample text, too, explaining ID, songs, and identifying birds in flight. To aid the user in general bird identification techniques the Stokes guide emphasized shape as the first ID criterion, before discussing color patterns. It is simply the best photographic field guide for North American Birds and competes nicely with the Sibley and National Geographic guides. [See my review of the 2010 guide.]

That said, however, The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds (Eastern Region and Western Region) is simply a marketing version of their landmark 2010 book. I understand the reasons for producing Eastern and Western versions of their popular field guide. At 800 pages, their original was too large to carry into the field. So it made sense to create less costly guides with 500 (Eastern) and 575 (Western) pages. There's nothing wrong with these guides--the praise for the original guide still applies. For these "new" versions, if a species occurs east of the 100th meridian the publisher took the species photos and text in toto from the continent-wide guide and put it in the Eastern Guide. Same for the Western guide west of the 100th meridian. The only changes are updates to some of the scientific names (no more Dendroica warblers) and a split that gave us back the gallinule.

Since there were no changes to the text and photos in the Eastern and Western versions (except for a juvenile Saw-whet Owl), it creates some real oddities. For instance, of the five subspecies of White-crowned Sparrow, one subspecies occurs in the East, four in the West. However, the Eastern field guide shows photos of 2 Western subspecies and describes them in the text. Photos in the Eastern field guide of Song Sparrow show two from California, one from British Columbia, and one from Alaska--all of forms that look significantly different than Eastern forms of Song Sparrows. The Eastern guide describes 17 subspecies of Fox Sparrows in 4 groups, but only one subspecies of Fox Sparrow is found regularly in the East. Five of seven photos of Fox Sparrows are of forms that do not occur in the East. I think it would have been less confusing to show only the forms found in each region. It would have saved many more pages of the field guides, especially in the East. Perhaps more photos of different plumages of the correct subspecies could have been shown instead.

If one already owns the 2010 Stokes Field Guide to North America (north of Mexico), then I see no benefit to purchasing one of the regional guides. However, these regional guides are smaller and lower priced than the original. If one does not own the 2010 version then they should very definitely pick up the original or one of these "new" 2013 regional guides. They'd make great gifts.

The reason the 2010 Stokes guide was so good was that it used numerous photos of different plumages. Additionally, it was the first field guide to really describe all the variations of subspecies--with photos of many different-looking forms. The book had ample text, too, explaining ID, songs, and identifying birds in flight. To aid the user in general bird identification techniques the Stokes guide emphasized shape as the first ID criterion, before discussing color patterns. It is simply the best photographic field guide for North American Birds and competes nicely with the Sibley and National Geographic guides. [See my review of the 2010 guide.]

That said, however, The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds (Eastern Region and Western Region) is simply a marketing version of their landmark 2010 book. I understand the reasons for producing Eastern and Western versions of their popular field guide. At 800 pages, their original was too large to carry into the field. So it made sense to create less costly guides with 500 (Eastern) and 575 (Western) pages. There's nothing wrong with these guides--the praise for the original guide still applies. For these "new" versions, if a species occurs east of the 100th meridian the publisher took the species photos and text in toto from the continent-wide guide and put it in the Eastern Guide. Same for the Western guide west of the 100th meridian. The only changes are updates to some of the scientific names (no more Dendroica warblers) and a split that gave us back the gallinule.

Since there were no changes to the text and photos in the Eastern and Western versions (except for a juvenile Saw-whet Owl), it creates some real oddities. For instance, of the five subspecies of White-crowned Sparrow, one subspecies occurs in the East, four in the West. However, the Eastern field guide shows photos of 2 Western subspecies and describes them in the text. Photos in the Eastern field guide of Song Sparrow show two from California, one from British Columbia, and one from Alaska--all of forms that look significantly different than Eastern forms of Song Sparrows. The Eastern guide describes 17 subspecies of Fox Sparrows in 4 groups, but only one subspecies of Fox Sparrow is found regularly in the East. Five of seven photos of Fox Sparrows are of forms that do not occur in the East. I think it would have been less confusing to show only the forms found in each region. It would have saved many more pages of the field guides, especially in the East. Perhaps more photos of different plumages of the correct subspecies could have been shown instead.

If one already owns the 2010 Stokes Field Guide to North America (north of Mexico), then I see no benefit to purchasing one of the regional guides. However, these regional guides are smaller and lower priced than the original. If one does not own the 2010 version then they should very definitely pick up the original or one of these "new" 2013 regional guides. They'd make great gifts.

Labels:

bird books,

reviews

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)